When IBM Fellow Ranjan Sinha first heard about UC Berkeley's Data Science Discovery program, he thought of mangrove trees. Sinha, vice president and chief technology officer for the IBM Global Chief Data Office, is from the region surrounding the Sundarbans, an area in India bordering Bangladesh and West Bengal with one of the largest mangrove forests in the world. In coastal habitats, mangroves account for 14% of the global oceans' carbon sequestration, and mangrove forests such as those found in the Sundarbans, the Mississippi River delta, and along the Amazon River sequester more carbon each year than any other ecosystem on the planet.

Sinha saw the Data Science Discovery program as an opportunity to mentor Berkeley's up-and-coming data scientists and investigate the intersection of mangrove forests and climate change. This is IBM's first project with the program, which pairs undergraduate data science students with partners in industry, government, academia and nonprofits for semester-long research projects. Sinha hopes the research will shed light on how changes in weather patterns are impacting mangroves and identify conditions that make mangroves more resistant to climate change.

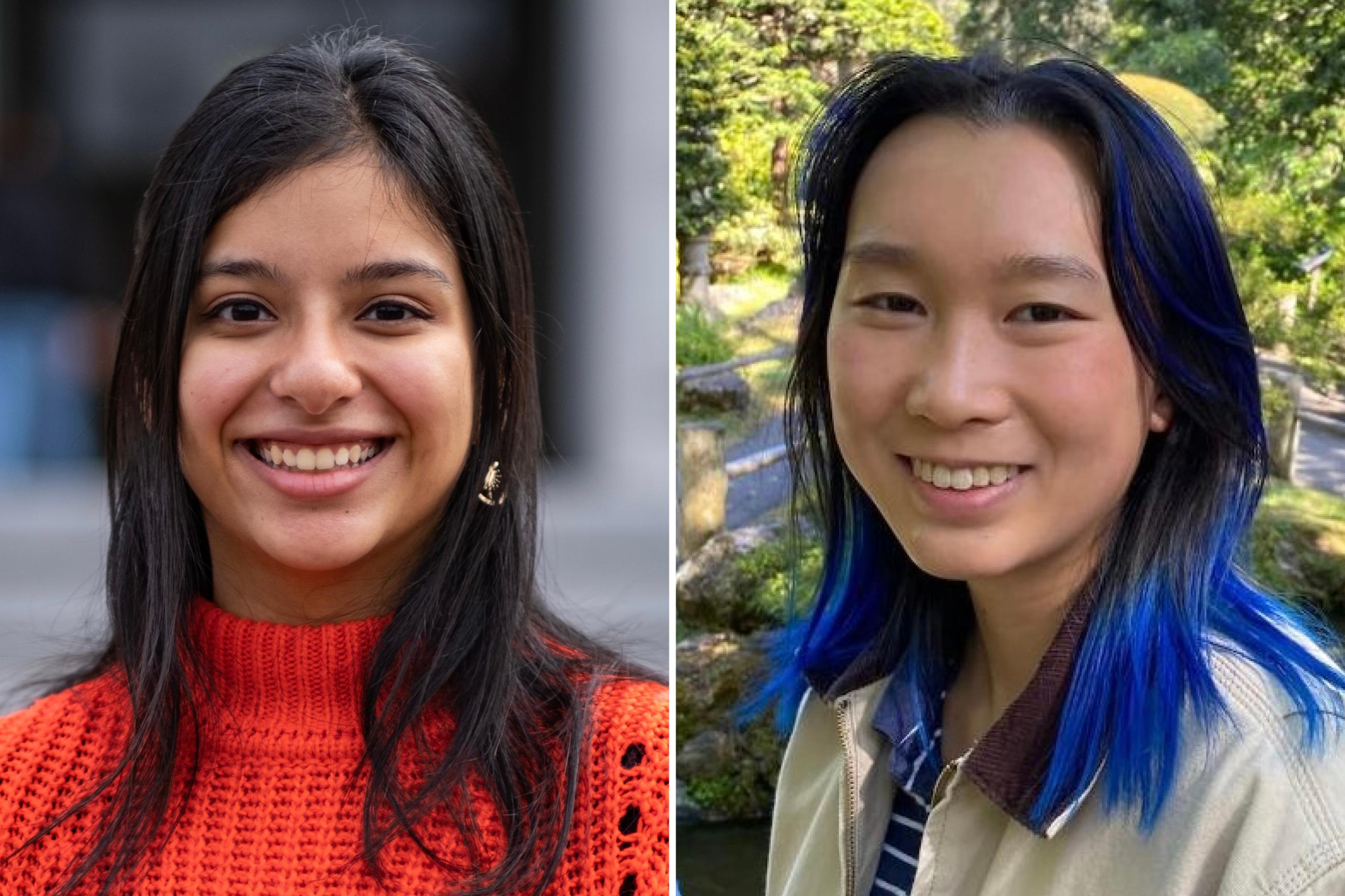

"Mangroves help with carbon sequestration and are a key resource for biodiversity, so it's really important to see exactly what kinds of effects climate change is having on them," said Lori Khashaki, one of six Berkeley students who participated in the project led by Sinha and Karina Kervin, a senior data scientist in the IBM Global Chief Data Office. A double major in data science and business, Khashaki says her education in California public schools instilled her with an interest in the environment and a desire to find ways to mitigate climate change. The IBM project offered Khashaki and fellow students Isha Arora, Michelle Cheung, Srihitha Kariveda, Grant Wagner and Catherine Wang an opportunity to build on such interest.

Mangroves are referred to as carbon sinks because they pull carbon dioxide from the air and store it in their roots, branches and surrounding sediment. Mangroves are one of the major blue carbon ecosystems (i.e., marine and coastal carbon-sequestering ecosystems), which store up to 10 times as much carbon as rain forests and other green carbon ecosystems.

"When I was younger, I did a volunteer project in Cuba replanting mangrove forests," said Wagner, adding that his earlier experience provided helpful context for understanding the project's geographical data. "I got to talk to locals there about how storms had decimated the forests and also just the role of mangrove forests in the ecosystem."

Grappling with real-world data

Sinha said the group faced challenges familiar to data scientists in industry – from provisioning storage and computing resources that can handle huge datasets to cleaning the data. "Working with a company is very different from doing class projects," noted Kariveda. Compared to real-world data, Arora observed that classroom data is like a "tightly wrapped package you're given that you only need to figure out how to unravel." She added that real-world data is much more complex, and there isn't only one way to untangle it.

The students grappled with data in unfamiliar formats and file sizes so large that they crashed their computers before the downloads could complete. Cheung said that one dataset she worked with had about a million rows of information. The team did research to understand the variables presented in datasets, and they experimented with synthesizing datasets with some challenging differences – for example, all the mangrove data was in an annual timeframe, and all the weather data was at a much more granular level.

Kervin said that these challenges of wrapping one's head around data and cleaning it are common in her work as a data scientist. "That's a major part of my job," she explained. "Sometimes it's the part that I really like because once I get down deep into the data then I have a better understanding of it. Unexpected things pop up, and I explore them."

Ultimately the team created visualizations that show Senegal mangrove loss over time, looking at different reasons for the loss and how land is converted after loss.

Access and opportunity through Data Science Discovery

Both Kervin and Sinha are committed to mentoring STEM students and were excited by the team's passion for the project. They were also impressed by how proactively the students responded to challenges and how well they worked together.

"There's been collaboration across several aspects – the provisioning, dividing and conquering the data, playing with the data, creating the posters and planning the presentations," Sinha noted. Fittingly, at last week's Data Science Discovery Showcase, the students won the Team Collaboration Award.

In addition to technical skills and professional experience, students said the project helped them learn how to communicate better with others in a group and how to schedule their time more efficiently. They learned how to balance biweekly project meetings and make progress between meetings while attending classes, completing coursework and participating in other clubs and activities.

Arora noted that half the students on the team are members of Women in Computing and Data Science at Berkeley, a student-run organization that provides mentorship and networking opportunities for women and non-binary students. Arora sees Data Science Discovery as offering a more equitable pathway to internship experience. With so many students interested in data science, Arora said it can be difficult to find an entryway to research opportunities, leading to a vicious cycle where only those with prior experience stand a chance. She noted that you often need to build a rapport with a particular professor to gain crucial research opportunities, which can be especially challenging at a large university.

"With this program, you apply and get in based just on the amount of passion you have or the skills you have," Arora explained. "It's not based on a professor's bias or whether they like your personality. That kind of equitable access is important."

Cheung added that diversity and equity in STEM have huge impacts because it's empowering to see representations of yourself in your field. “As a queer, Asian American woman, I’m just happy that I see myself represented in that way at Berkeley,” she said. “It also makes it more safe to pursue data science and feel like I belong where I am.”

A closer look at mangroves

While this was IBM’s first partnership with the Data Science Discovery program, Sinha and Kervin are already looking toward the next cycle to build on the foundation developed this semester. The team narrowed the scope of their analysis to Senegal, but Sinha and Kervin would like to look at other countries and also contribute to better understanding the impact of rising sea levels on mangroves.

Sinha said it's necessary to grasp the global changes in mangrove populations to identify the various patterns at play as well as corrective measures that have proven effective. He hopes that a bird's-eye view will enable an analysis not only of the conditions leading to mangrove loss, but also the steps that can mitigate this loss and where remedial measures could be effectively implemented.

"We wanted to work on the problem of the century, and we wanted to see what Berkeley had to offer through this program," said Sinha. "Our first experience has been fantastic, actually. It's enjoyable to work with these really motivated students."

"I'm just looking forward to the next round," said Kervin.

Before the Data Science Discovery cycle begins next year, Sinha will return to his personal inspiration for the project. "I'm motivated enough to now visit mangroves, which is where I'll be in January. I'll be visiting the Sundarbans for three days to get a closer view, which will help inform future projects."

This was one of 80 Data Science Discovery projects in the fall 2022 semester. To learn more about Data Science Discovery, visit the program website.